Though bearer of the name Butler, I could only imagine Uriah “Buzz” Butler (January 21, 1887 – February 20, 1977) uttering the sentiment, precisely: “We have been the butlers of our colonial masters’ house for too long, it’s about time we seek to own our place of homestead.” That place of homestead is obviously these islands on which our fore-parents were brought to toil from sunup to sundown with very little in return for their abundantly productive labor. And even when we were granted independence by Great Britain in 1974, there were still little to show for the hundreds of years our ancestors labored on the many plantations on these islands that comprised of the state of Grenada: not in the form of human capital development, nor in terms of infrastructure development, nor in terms of hard currency in our national treasury, in which to invest in our social development as a nation after the colonial era would have ended. No reparation was offered; and now finally, we are seeking, after thirty and forty-odd years, to make an official demand under the auspices of Caricom through the British court system, the same one that afforded compensation to the British families that were disadvantaged monetarily with the end of chattel slavery in the Caribbean.

Thus, imagined or unimagined on our part, this opening statement is a very important one to reflect on in this current period, for we are still faced with a situation of stark dependence as a so-called third-world nation. The situation is, in fact, one that is rather precarious, in a global environment of increasing strife, socially, economically, politically, militarily, and environmentally.

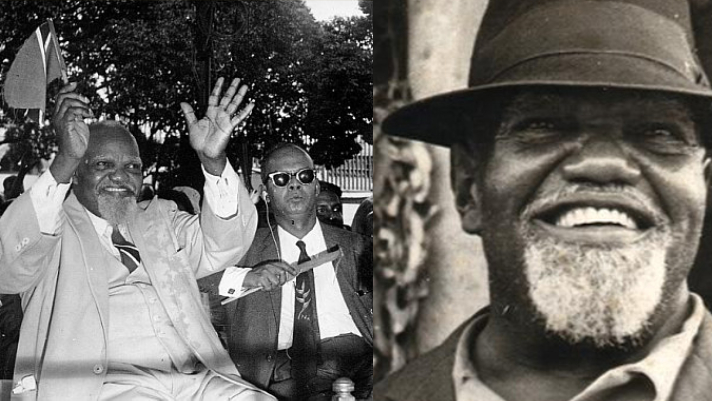

The Butler Plan/Project, which was initially unveiled just over a week ago on websites IAmGrenadian.com, and BigDrumNation.com under the heading A Viable Plan for Grenada, is designed to directly address our precarious place in this world. Moreover, it is most fitting, in both symbolism and substance, that such a masterful plan and project be named in honor of a son of the soil who made it his mission to promote the interest and general welfare of workers and citizens of both his homeland of Grenada and adopted Trinidad & Tobago, where he later made his home as a young man seeking to make his way in the world some three years after returning from fighting in the First World War as a member of the British West Indies Regiment stationed in Egypt. He had volunteered to fight for the British Empire as his way of addressing his immediate plight to find employment and material sustenance — fighting for the “mother country” was the refrain of the time.

Unmistakably, those same push factors that led Butler and others to leave their homelands are still very present even in today’s context, with whole families through chain migration uprooting to seek a materially-stabled life in the US, Canada, and Europe, taking with them the resources that would have been invested in their education and other social programmes.

One may be quick to mention that our young people are also gaining an education through the many scholarships sponsored by foreign governments in the current context. But one only need to view the reality on the ground to realize the true state of affairs: That our two current largest sectors, education and tourism, are principally the products of direct foreign investments, of which we are not the major beneficiaries by comparison; and that there is very little opportunities by way of employment for our secondary and college graduates in our service-based economy. Our national unemployment rate has been hovering over twenty-five percent for decades. Essentially, how does this reality factor in our development, when we cite the five percent economic growth witnessed in recent years, to ascertain the trajectory that we are embarked on? By all estimates, it is more than fair to say that though political independence was obtained in 1974, we as a people are yet to free ourselves where it matters most to any freedom-loving people: economically. Hence, the centrality of workers in this conversation of national development, as it was for the chief servant of the people, as he was illustriously referred.

The political organizations that Butler established in Grenada and Trinidad & Tobago all aimed to secure self-governance and a better welfare for citizens, which is suggestive in their given names: The Grenada Representative Movement, the Grenada Union of Returned Soldiers; the British Empire Citizens’ and Workers Home Rule Party, which eventually became the Butler Home Rule Party, and finally The Butler Party. The mantle to ensure that our people are secured in an increasingly complex and competitive global environment is left with us, and it requires a new approach to national development. What is not new, however, is that the focus ought to remain the backbone of any nation, the workers in the fields, factories, hotels, classrooms, and offices of our tri-island state.

Butler, perhaps more than any other in the social and political life of the Caribbean (certainly in the modern era), demonstrated the deepest understanding of such through his organization and mobilization of workers in this struggle. The workers of the oil fields of southern Trinidad heard the call of their humble servant in 1937 to join him in a labor movement as they ought to, to make demands in the interest of improving their lives as workers and also as citizens. It was only natural that Butler would seek to galvanize the entire population of Trinidad & Tobago by forming a political party to contest general elections when the changes to the society were much too slow. Butler did not have the kind of success in electoral politics in the colonial period, outside of the leadership he provided in winning universal suffrage in 1945 in his push for home rule, as he did in the labor movement, but he would have left an indelible mark on the landscape of his adopted homeland for posterity. So much so that that country’s major thoroughfare, once named in honor of a member of the British Royal family, bears his name: Uriah Butler Highway. Butler was also bestowed with the Trinity Cross in 1970, the highest honor in the Republic of Trinidad & Tobago. June 19, the date of the Oilfield Workers’ hunger strike and riots, was declared a national holiday in 1972. On February 24th, 1977, Butler was given a State Funeral, and was buried in his home district of Fyzabad.

Butler sacrificed his entire adult life fighting for those causes, which are best distilled in the words self-governance, and a dignified people rooted in their own sensibilities and cultures. In that vein, it is paramount that our approach to social development is tailored to provide reparative justice for the grave harm done to our people. Hence, the kind of social investment that is proposed herein is one that seeks to give the biggest support to individuals and their families, and ultimately our collective existence in the society that we aim to make more industrious and sustainable for many generations to come. The targeted aim of this plan is to figuratively and literally provide a floor and a roof to our workers from which they can be empowered to live purposeful lives, and affirm their humanity in a manner that will build a rich social and economic environment, not to mention a more agile and responsive democratic society.

As such, in the midst of our relative poverty as a nation, we seek to provide security to workers and their families through a home development programme, whereby workers will be granted a house in the value of approximately $100,000 to $120,000, at an annual cost to the government of $100,000,000 to $120,000,000. Twenty thousand homes will be constructed over a twenty-year period, at the rate of two hundred and fifty houses constructed every three months. The general cost of this project is projected at two billion to two billion four hundred million, depending on the unit cost established. The revenue streams projected to be used are the current citizenship by investment program which is already raising hundreds of millions, as well as the anticipated revenue from the production of oil and natural gas. Another viable revenue stream would be that of tax revenues from the tourism sector, with the curtailing of the extended tax holidays currently afforded to prominent constituents of that industry (20 plus years being the norm).

Why isn’t this proposal a popular idea at present, you may ask? It is because we are not wired to engage in that way of thinking, of viewing ourselves and thus responding to the given market realities and competitive mode of relating to one another than we already do — struggle for our own, individually. The kind of protection that I am espousing can only be realized on the basis of a shared or collective effect or experience, one that obviously curbs competition for a most basic element of social life, a home. It means workers of our humble nation-state will be working to live purposefully, with the greatest hope for self-actualization, in all sense of the term. They would have been given a floor to stand on and a roof over their heads, figuratively and literally.

Indeed, such a project would serve as the biggest and most comprehensive development to our human resources and our living habitat. It will spur growth internally and externally for our people. For one, it has the capacity to create 100 percent employment in the country and boost the spending power of citizens in a manner we have never witnessed. This could very well be our most immediate engine for growth, socially, economically, and psychologically, should we act on it with great intentionality, to realize its impact on all aspects of our lives as individuals and nation.

I am ready to witness such a comprehensive and protective approach to national development. It is doable, and it worth every cent that will be invested: for our physical health and our general well-being as human beings with creative energies to propel our existence on a level that will sustain economic and social growth for many generations to come. It is the kind of reparative justice we can give to ourselves as citizens of a beautiful country. The responsibility is squarely in our hands as workers, as citizens of Grenada to bring this viable plan and project to fruition.

Put simply, our destiny as a people is to give fuller and thus better definition to Home Rule, to continue the good fight for a better way of existence.